In 2019, RCMP in the Northwest Territories used force 116 times — the highest total in the last three years.

In 2018, officers used force 70 times and 90 times in 2017.

Earlier this year, the Globe and Mail published an article on national RCMP use of force statistics. CKLB requested those numbers for police in the NWT.

The report says ‘G’ division RCMP logged an average of 38,000 calls annually between 2017 and 2019. Of these, about 42 calls resulted in the need to use force — about one time for every 904 encounters, or 0.1 per cent of cases.

According to the RCMP, this frequency is about the same as the national average.

Higher involvement of guns

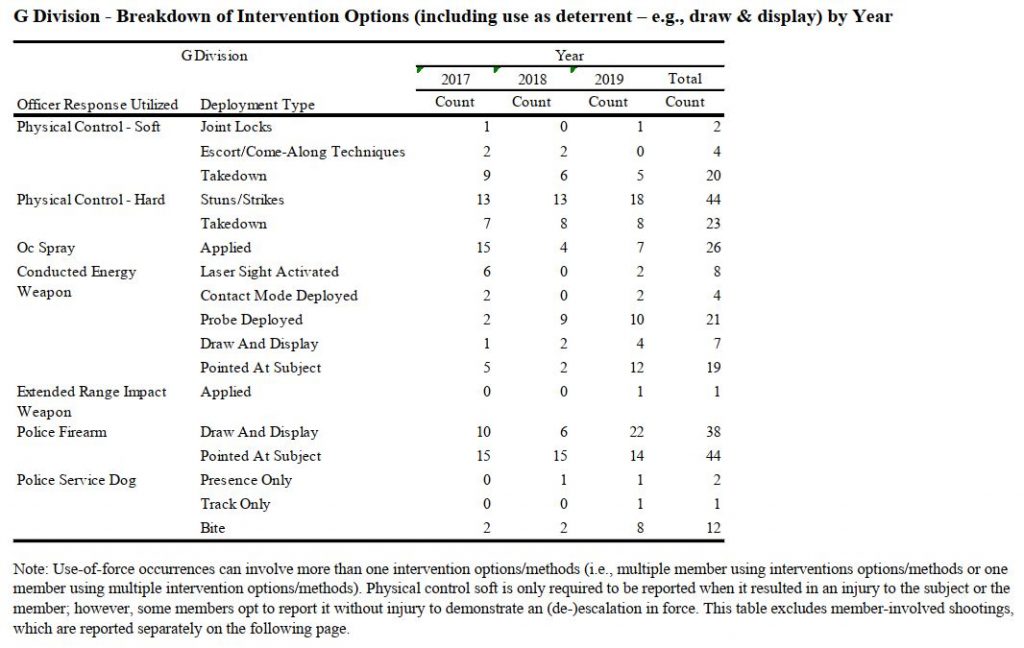

The RCMP breaks down its use of force by “intervention options”.

One of the notable changes in 2019 came in the “Police Firearm” category. The number of times officers drew and displayed their weapons jumped from six in 2018, to 22 in 2019; the number of times officers pointed those guns at residents remained steady at about 15 every year.

The report also says no officers have been involved in a shooting in the past three years.

The RCMP currently has a pilot program using Extended Range Impact Weapons (ERIW). These weapons fire sponge-tipped rounds “in an effort to provide additional less lethal options to our police officers and enhance public and police safety,” says Robin Percival, national RCMP spokesperson.

Marie York-Condon, the spokesperson for NT RCMP, says local police are “participating in a limited manner” in the pilot program. There are only eight ERIW in the NWT. She said NT RCMP are leaving it up to headquarters on whether the pilot will be successful or not.

She added officers use ERIW to “respond to a subject who may be intent on harming themselves or others”. The RCMP says this strategy is meant to give more time for de-escalation before lethal force.

However, this tool was only used a single time last year.

Taser use and ‘hard’ physical control up, ‘soft’ physical control down

The number of times police used conducted energy weapons, commonly known as Tasers, in 2019 was also the highest in three years.

While the contact mode was only used twice, the probe deployment, draw and display and number of times officers pointed Tasers at people all went up since 2017.

All categories of “soft” physical control have gone down since 2017, as well as the RCMP’s use of OC spray, commonly known as pepper spray. However, the number of “hard” physical control methods have gone up (stuns/strike) or remained consistent (takedowns), in that time.

The full breakdown of intervention options can be seen below.

Percival says the RCMP’s reporting is meant to capture when an intervention method is used as a deterrent, in addition to when it is “applied” to a person. Basically, even if one of the intervention methods is physically used on someone, it still has to be reported. There can also be multiple intervention options used during a single incident.

Asked about the overall increase in use of force methods from 2017 to 2019, York-Condon told CKLB, “Data sets often have to be looked at over a longer term where a small spike can be temporary, or require more time to become established as trends.”

The police’s use of force gained much attention earlier this year following weeks-long anti-racism demonstrations in the wake of the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man in Minneapolis, at the hands of police. Demonstrations spilled over borders with a handful happening in the NWT. Soon after the Yellowknife gathering, NT RCMP Chief Supt. Jamie Zettler held a news conference to address the issue.

Caroline Wawzonek, minister of Justice, has previously said her department does not have operational control over RCMP in the territory.

Police dogs

NT RCMP got a second police dog handler in December of last year. Last year, there were more incidents of police dog bites, going to eight, up from two the previous two years.

According to York-Condon, police dog services was deployed on more than 160 calls last year, with 21 of them being for missing, lost or suicidal people.

Asked what the rest of the calls were for, York-Condon said the dogs’ roles vary widely, from tracking a fleeing suspect, to assisting in an arrest, to searching for evidence.

Given this, CKLB asked why so few of the 160 calls last year were represented in the data received. York-Condon referred the question to the national unit.

Initially, Percival said the presence of a police dog would not be enough to make officers file a report. However, under the “Police Service Dog” category, there is a section specifically for “Presence Only”. Percival later clarified that for an officer to file a report under this section, the handler “announces to a subject that the police dog will be used” but never actually lets the dog loose.

According to the data, this happened only a single time in over 160 calls last year.

Assessing and reporting

RCMP officers are trained to respond to situations using the Incident Management Intervention Model (IMIM).

Officers must also go through annual IMIM re-certification.

The numbers above are based on Subject Behaviour Officer Response reports (SB/OR). Percival says officers must file these reports if they use “soft” physical control that results in injury, “hard” physical control, use a weapon (including drawing it from a holster) or engage police service dogs.

As part of the report, officers must log “environment, situational factors, what substances and weapons were present, a description of the subject’s behaviour and the officer’s corresponding response, injuries and a short description of how the event unfolded”.

However, as reported by the Globe and Mail, “The RCMP does not collect data on race or Indigenous status.” And, “neither the (federal) government nor the RCMP has made a firm commitment to begin reporting such data.”

CKLB asked RCMP headquarters whether there are any oversight mechanisms to ensure officers are reporting all use of force.

We were told officers are required to file an SB/OR report within 48 hours of such an incident.

“Failure to complete an SB/OR report could result in internal discipline processes or initiation of a code of conduct review,” says Percival.

Asked what mechanisms are in place to ensure complete reports, Percival said all reports go to an officer’s supervisors, which can ask for more information.

York-Condon said NT RCMP “welcomes independent police oversight”. Despite there not being an official process for this kind of oversight in the NWT, she says senior management will engage other police agencies or mechanisms “where appropriate”.

CKLB asked whether police divisions need to report increased use of force, or whether there is a trigger for such a process.

“Senior managers of the NT RCMP may in fact engage, report and respond to trends within their respective areas,” said York-Condon. She added, “in general, only a large occurrence, such as an incident in which use of force was highlighted, would a separate review mechanism be generated”.

Below is the full report obtained by CKLB.

G Div - UoF Stats and Trends - 2017-2019