Until recently, Brandon Buggins didn’t really know the other men in his community, even the ones he would casually greet out in public.

Buggins was a closed book too, even when struggling with mental illness, addiction, and the pressures of fatherhood: “It’s really tough to be able to come out of your shell and ask for help when, I know for myself, I was always taught not to show my emotions, not to cry,” he says.

That was until he started a men’s group in his home community of Fort Simpson late last year. He soon learned that he might have felt isolated in his struggles, but he wasn’t alone.

The statistics

For men in the N.W.T., the statistics are grim.

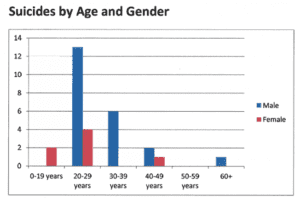

Suicide statistics for 2021-22 were so alarming the N.W.T’s chief coroner chose to release them early last year. As of October 2022, 18 suicides had been recorded for 2022, a significant increase over the 11 that were documented the year before, and the highest number in at least 20 years. The victims of this epidemic were mostly young — and male.

(Office of the Chief Coroner)

According to the statistics, 76 per cent of suicides in 2021 and 2022 were men. The mortality gap between men and women extends beyond suicide as well: Between 2019 and 2021, the average life expectancy in the N.W.T. was more than four years higher for women than for men (78.94 years compared to 74.59).

On the education front, across the three territories just 39.2 per cent of those who graduated postsecondary in 2021 were men, and just 40 per cent of postsecondary degree holders were men.

Men in the N.W.T. also have a higher rate of unemployment than women— that is, they are more likely to not have a job despite actively looking for one. In 2022, 6.7 per cent of men in the N.W.T. were unemployed compared to 3.2 per cent of women.

And education and employment are connected: In small communities in particular, “a lot of the work that is available right now is teachers, nurses,” says Buggins. “There’s a lot of specific training that you need to do for these type of jobs and it’s not available for absolutely everybody.”

Men in the NWT are also less likely to report a sense of belonging: 76.4 per cent of men compared to 82.4 per cent of women in 2015-2016, according to the territory’s most recent health status book. “I noticed in smaller communities such as here, we have sewing circles, they have women’s nights, more [activities] catering to women’s needs,” says Buggins. “And I found that there’s a huge gap there: There’s nothing for men to do during the evening.”

Men’s groups answer the call

When the Fort Simpson men’s group first started, Buggins says it was tough to break the ice. “Everybody knows each other, but you don’t really know each other, because you see each other in the community all the time, but you just do small chat.”

Eventually, the group became a forum for members to talk about everything from sports to movies to more personal subjects, like addiction. The group even hosted an addiction councilor at one of its meetings.

“It allowed me to navigate what I was going through, because I was able to interact with [someone’s] story and take pieces from it and add it to mine and be like, ‘I can really relate to that,” says Buggins. “Because you’re so much older than me, this is the direction I should probably take, because this is potentially what my life can be.”

Other groups have sprung up across the territory as well: Johnny Ongahak, a certified life coach, is one of the founders of Yellowknife’s Northern Brotherhood of Men. When it was founded in October 2022, he says, the goal was to help men become allies in the fight for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. But he says the group is also a forum for men to express themselves, perhaps for the first time. “They’re trying to encourage other men to come with them, and they’re like, ‘Oh, no, I’m okay.’ And here, this guy is going through a really bad divorce, and he’s staying with his mom, and he’s in his 40s.”

(Facebook photo)

Each week, about 5-10 men, mostly in their late 30s and early 40s, attend the group. Ongahak says he wants to see those numbers go up.

Another former Yellowknife men’s group, “Answer the Call,” is no longer active. But during the eight months it was running, it was operated as a space where men could help each other become better allies in opposition to violence against women through discussion and mutual accountability.

Eventually, attendance dwindled, and they could no longer justify the cost of keeping the group running, says organizer Jay Boast. But he hopes the group will one day see a resurgence.

The Fort Simpson men’s group is no longer active either, due to a lack of funding. But Buggins is also hopeful the group will meet again one day.

Similar groups were at one point active in Hay River and Inuvik: In Inuvik, a men’s group called “The Cabin” was formed in 2021 to unite men in the community around social activities. Another “Answer the Call” group was also formed in Hay River. (The organizers of both groups did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Supports, or lack thereof

Boast also has his own experiences accessing mental health services in the territory, which he says was a challenge. He remembers a time when he was uninsured and on the waitlist for counselling. “At that time, I was told that the wait would be at least three to four months. It ended up being closer to six months before I saw someone. And it became very clear that the approach was to try and give me some tools, but then to send me off on my own because of the volume of people who needed to be seen. There just weren’t the resources in place for ongoing care.”

Based in part on his own experiences, Boast feels there ought to be a greater investment by the territory in mental healthcare. But Boast also sees personal responsibility as playing a key role in shaping good men. “If I was going to ask for men to be more accountable, I had to take on that task myself. And, when looking back, there were times I could look back and think about behavior that I wasn’t particularly proud of, and actions that I wish I could take back.”

Some territorial funding has also been set aside to help men recover from past traumas: $292,000 annually goes into the territory’s Men’s Healing Fund. The purpose of this funding is to offer the opportunity to “deliver community-based Men’s Healing programs,” according to the GNWT’s website. The fund has managed to survive in recent years despite almost not having its funding renewed in 2016.

For his part, Buggins has a message for all the men out there: “If you’re struggling, or if you’re just down and out, it’s better to reach out instead of reaching out for something that’s just going to be doing more harm, or adding more fuel to the fire,” he says. “Just know that you’re not alone, because it’s a struggle at times.”

And, he says, there are plenty of resources men can access, including community counselling, treatment facilities, and help lines.