“I was taught (to be) ashamed of myself or I watched what I did or what I said simply because of the way it was in the residential schools,” says Eileen Beaver, a 68-year-old Elder from the lost community of Rocher River.

At the age of eight, Beaver was displaced from her home, sent to a Day School in Fort Resolution, and later spent four years at Breynat Hall in Fort Smith.

“I found it really affected me because (I was) speaking English a lot (and) thinking English. I started talking less and less Dene,” she says. “I almost lost it.”

In the home and on the land, Beaver spoke Dene Dedlıne, Gaelic, French, Cree, Michif and Latin long before English was introduced. During the fur trade, she says it wasn’t uncommon for people to speak several languages.

With over 25 years in education, Beaver dedicated herself to the preservation of her Dene tongue, advocating for youth, culture, and tradition one syllabic at a time.

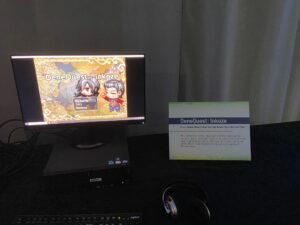

Now Beaver alongside Kyle Napier have teamed up on an interactive land-based video game called DeneQuest (Inkoze) to help bridge the gaps for students.

Down in Toronto earlier this month Napier and Beaver had an opportunity to showcase DeneQuest at Imagine Native. (Photo courtesy of Kyle Napier)

Napier is a 34-year-old instructor and game designer at the University of Victoria who at the time was getting language lessons from Beaver.

Over three years ago, Beaver actually instructed Napier to create the game.

“It’s a 48-bit game,” he says, “It looks like a game that came out in the early 90s, kind of Zelda style; Lots of kids have told me this looks like Pokémon or Harvest Moon.”

The player sets out on a journey to reclaim Rocher River, gaining animal friends along the way like a raven, lynx, pike, wolf, and even rez dogs. When traveling through the communities of Łutsël Kʼé, Hay River and Fort Resolution, the Elders share how much they miss Rocher River and in turn their traditional tongue.

In 1960 the only school in Rocher River burnt down, and many like Beaver were forced to relocate.

With the inception of its first trading post, the community was thriving until a series of unfortunate events, like a fire, flood, and closing of the post brought down Rocher River. Residents ultimately had to abandon it.

Napier says, “It was a community where people spoke Dene Dedlıne, So it’s a real place of significance for the language.”

“This game is a journey back to Rocher River,” he adds.

After hearing Beaver’s story, he says, “I kind of want this game to be like a gift to the Elders.”

(Photo courtesy of Kyle Napier)

Although the game was meant for classrooms, Napier says it was actually designed for somebody like himself: someone who didn’t grow up with language speakers. “I didn’t grow up around my language at all, actually. ” After trying some Dene-based language apps, he noticed how unnatural it felt to use words singularly instead of in complete and immersive sentences.

“It’s important that we do this work now because the languages are threatened and everything is contained in the language, from worldview to knowledge perspective, even to relating with the land,” says Napier.

With over 100 mini-games to complete, DeneQuest is still in its prototype stage and awaiting game testers before its release.

A recent study by Stats Canada found a decline in Indigenous people who feel confident using their mother language, although the report does show a growing trend of Indigenous people learning their language as a second language. While First Nations in the Northwest Territories still hold the torch for most language speakers in the country, that number is declining as well.

Napier argues that youth are interested in pursuing their language; However, they’re not being met with adequate learning opportunities.

“There was a gap, because of residential schools, because of intergenerational trauma and shame from colonization,” he says. “But now youth want to learn and it’s hip and it’s cool.”

“Indigenous languages are cool, they’re really cool,” he adds.

Napier stresses that technology is just one small piece of revitalizing language. “Getting out on the land surrounded by language speakers, that is the best way to learn,” he says. And Beaver invites everyone to try.

“You don’t have to be Dene to know how to read and write and understand the language and culture. But if you’re interested, you know, why not?”