Warning, this article talks about abuse at residential schools.

Catherine Boucher, an Elder from Fort Resolution, says her first language was Dëne Dédliné Yatıé.

“When I went to residential school, I couldn’t use my language,” she says, “the nuns used to hit my forehead… So I was scared to talk.”

Now she has been relearning her language — one that very few people speak.

Capstone project

Boucher, a Tetsǫ́t’ıné Elder, was among 12 participants of a capstone project on how to acquire, revitalize and reclaim Dëne Dédliné Yatıé.

Kyle Napier, of Fort Smith, is the author of the project which he submitted to the University of Alberta for his Master in Arts.

Napier says an interesting aspect to the project is that no linguist formally acknowledges it.

He says its often referred to as Chipewyan which encompasses Dëne Sųłıné Yatıé, another similar but distinct dialect from Dëne Dédliné Yatıé.

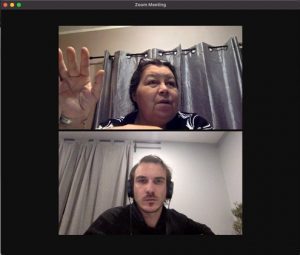

Top: Eileen Beaver, an Elder and fluent speaker of Dene Dedline Yati. And Kyle Napier, who completed a capstone project on the language. (Photo courtesy of Kyle Napier.)

He says the differences are important.

“The whole project is about sovereignty, of our words and identification and our language,” he explains.

The project also discusses the language’s history.

The report says people from Rocher River, an abandoned community in the South Slave region, were recognized as Dëne Dédliné.

He says at one time, most people in Tu Nedhé spoke the language.

“Everyone spoke the language if you were in the area, and this language was in this region — according to the Elders — over the course of several ice ages,” he says.

Napier says he got the idea for the project from an Elder he considers a relative — Eileen Beaver.

Beaver was Napier’s Elder mentor for the project, putting him in touch with other Elders to speak with and reviewing the report three times before it was submitted.

Beaver, who lived in Fort Smith, speaks numerous languages including Dëne Dédliné Yatıé, which she is fluent in and has dedicated her life to teaching.

Beaver also worked as a teacher several schools in the NWT, where she taught the language to her students in creative ways.

“We tried to do a lot of things with technology so that kids or students who are learning the language would feel that it isn’t just old school,” she explains.

This includes using apps and different games.

But she also used music.

“They would also do rapping… It was amazing,” she says. “One student… Her biggest project was to do a rap song all in Dene Dedline Yati and then presented it to the students.”

Elders as knowledge keepers

A unique aspect of the 230 page report, is its inclusion of Elders’ knowledge.

“They openly spoke with him, talked with him, they gave their opinion, they gave their knowledge and you could feel it as you’re reading,” Beaver says.

The report was also reviewed by the Elders, including Beaver.

Napier spoke with fluent speakers and emerging learners alike.

But there were challenges.

“There aren’t many people who are literate in the language,” he explains, “that’s why there’s many different spelling conventions for the same word.”

This was where Boucher came in as she specializes in writing.

“He sends me a copy of his report and then I had to work on some of the Dëne Dédliné words,” she explains. “So he could have them right in his report.”

The project also had some logistical challenges brought on by COVID-19.

“I can’t go visit in person,” he says, “all of the interviews were held in my, in my truck, because I had the best audio that I could get.”

Indigenous language funding

The project received $5000 in funding from Northwest Territory Métis Nation under the Indigenous Languages Program.

“I used every penny of that grant towards funding Eileen as the Elder mentor who reviewed the whole thing, probably three times,” Napier says, “as well as all of the fluent speakers and language learners.”

Napier credits the Northwest Territory Métis Nation for supporting his work and adds there is good work being done in the territory. This includes the department of Education, Culture and Employment providing territorial funding towards Indigenous languages.

But he adds a lot more needs to be done.

Recommendations

The report includes recommendations from the Elders for the federal government, territorial government and Indigenous governments.

Catherine Boucher is an Elder who has relearned her first language Dene Dedline Yati. (Photo by Nadine Delorme.)

Recommendations to the federal government include paying families to learn Dëne Dédliné Yatıé acknowledging it as a language and compensating the families of Rocher River.

For the territorial government, they recommend it involve communities when developing their Indigenous Languages Action Plan as well as fund childcare and Elder honoraria for learning the language outside of schools.

For Indigenous governments, they recommend they share cabins and camps to support learning Dëne Dédliné Yatıé as well translate and work with existing Dene Yati materials.

“Those recommendations need to be taken seriously,” Napier says.

Along with giving Elders the opportunity to provide recommendations, Napier says the project was important as it used knowledge Elders passed down.

“So it’s not just the results of this work and the recommendations, but really that about how it was done,” he says. “I cherish the opportunity to share these words from Elders.”

Although Dëne Dédliné Yatıé was her first language, Boucher says it has been a long process of re-learning it.

“It was pretty hard for it to begin, because I was so used to the English language,” she says. “And then I started with the vowels. I started saying the vowels every day, every morning.”

And slowly but surely, she relearned the language of her ancestors and is in the process of passing it on to the younger generations.

Luke Carroll is a journalist originally from Brockville, Ont. He has previously worked as a reporter and editor in Ottawa, Halifax and New Brunswick. Luke is a graduate of Carleton University's bachelor of journalism program. If you have a story idea, feel free to send him an email at luke.carroll@cklbradio.com