“I’m a hardcore Northwest Territories artist,” says Robert Burke. “It means I’m a fighter, my art shows that I fight.”

Artist and residential school survivor Burke, 80, paints his truth and life experience being “raised by institutions” in his latest piece submitted to Canada Post in the wake of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

The piece “was called Truth and Reconciliation and I figured I may as well tell truths,” says Burke.

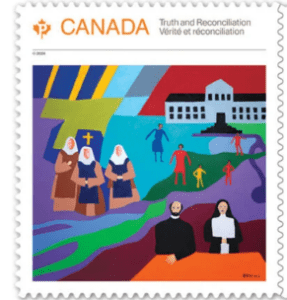

This is the third issue of the Truth and Reconciliation stamp series with the Survivors Circle. Burke is one of three artists apart of the Survivors Circle to be featured.

“I always knew I was gifted,” he said. “My art helped me in a lot of ways.”

Burke, originally from Fort Smith was abandoned by his mother due to the complex history surrounding the region and its relationship to Black American soldiers at the time.

Burke knew early on that he was different, being the son of a Black U.S. soldier and an Indigenous mother.

He was only four years old when he was shipped to St. Joseph’s residential school in Fort Resolution and later St. Mary’s Boys Home in Edmonton. He recalls being sent to a foster farm, where he worked as an unpaid labourer in his early teens.

Despite his circumstances, Burke recognizes the power and freedom his imagination granted him.

“There was a powerful part of my mind that kept me free, kept me open, so I was able to function reasonably well,” he says.

Now Burke uses his past as a way to reconcile his future through art.

“I try to say, there’s something positive to it. And there was because I came out the guy who I was; I’m a professional artist. I’m doing good. I’m not rich. I got nothing (but) I’m 80 years old and I’m still painting. I mean, you can’t complain about that.”

On a canvas of about 90 inches wide and 54 inches tall, Burke accentuates the gravity and influence the Catholic Church had during his youth.

Being an orphan, Burke had to rely on the institution to get by. Through this stamp and his other works surrounding his residential school experience, Burke can retell his story and take control of the narrative.

“I figured, you (guys) treated me this way, and you figured the story isn’t going to come out,” Burke said. “I’m the (guy) that’s going to tell it.”

The image depicts a residential school with a few children nearby, several nuns and authoritative figures overlooking them. In an abstract style, Burke uses color and form to cut through the dark and ugly and shed light on all the fascists of the institution.

“I make my work colorful even though I’m telling a nasty story,” says Burke.

“I just wanted to express the power structure of the residential school.”

“I was raised by nuns and it was a pretty brutal experience,” he says, “you’re a dark kid, you didn’t look cute like the rest of the kids.”

Burke remembers standing out from his peers with his darker complexion and curly hair. And that often didn’t bode well for him.

He recalls being beaten, ridiculed, verbally assaulted and ostracized among other things.

The feeling Burke says he hopes to evoke through the image is empathy.

“The reason I did the stamp wasn’t to blame anybody, but I just wanted to express a truth and part of that truth, that knowledge is the institution.”

He understands that his art is uniquely his own and that some people might not understand it. However, he’s sure people will feel something.

Burke sees himself, with a paintbrush in hand until his final days. “I want to know more about my mother,” Burke concludes.

Looking ahead, Burke told CKLB his next works will focus on his mother, his Chipewyan ancestry and the struggles of being a woman in Fort Smith in the 1940s.

This stamp series will also reflect the legacy of notable survivors Helen Iguptak and Adrian Stimson.

Robert Burke, Helen Iguptak and Adrian Stimson are featured residential school survivors and artists on the latest TRC stamp series with Canada Post. (Canada Post)

The booklet will be available online at postal outlets across Canada beginning on Sept 27.

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line provides 24-hour support to former residential school students and their families. If you require support, please call 1-866-925-4419.