For Cynthia Pavlovich, every day starts in Gwich’in (Dinjii Zhu Ginjik).

“That’s been a really nice start to the day,” she says. “I just want to learn so badly I am willing to invest any and all of my spare time in doing that.”

Pavlovich is 39 years old, originally from the Yukon, working in Yellowknife. This is her first time learning her mother tongue as part of the Mentorship Apprentice Program (MAP) with the territorial government.

Since starting her fashion business, Gwich’in Luxury, she says, “I was looking for ways to connect back to my culture and fill those spaces in my heart that I feel are kind of empty from the fallout of Residential schools. When I found out how endangered it was, it became a life goal of mine.”

Every Monday through Friday from 6 a.m. until 7 a.m., Pavlovich and her instructor, Eleanor Firth, meet virtually.

“It’s kind of like having a bonus auntie,” she says, “But one of the ones that have all the knowledge from the culture, which has been a really beautiful exchange. She’s become a very close friend of mine.”

Before this initiative, Pavlovich and Firth had never met but have since connected on a common goal – to keep the language alive.

Ten pairs are chosen annually to participate in the MAP. (Photo courtesy of Cynthia Pavlovich)

“We’ve covered all kinds of things from plants, animals, family names, simple greetings, numbers,” Pavlovich says, even things like translating the footer for her email, opening a meeting in prayer, or land acknowledgments.

Earlier this month, Pavlovich went so far as to put dozens of labels of common words and phrases all over the house, not only for her benefit but to get her kids involved as well.

“It’s in the bathroom, it’s in their bedrooms. It’s in the living room. It’s in the kitchen, everywhere,” she explains, “and it’s been a lot of fun. I’ve been trying to use the language in my home, in hopes of sharing it with my kids. And it’s kind of neat to see them starting to use it as well.”

As part of the (MAP) after three years, Pavlovich will be able to take the reins and mentor a student of her own.

“Even if it’s just simple numbers or greetings, just getting the language used more often is going to help save it, right?” says Pavlovich.

One of the ways Pavlovich is bringing Gwich’in to life is through a Christmas chillig singing group with the Gwich’in Tribal Council. Not to mention a new children’s book and traditional poem to be published in the coming months.

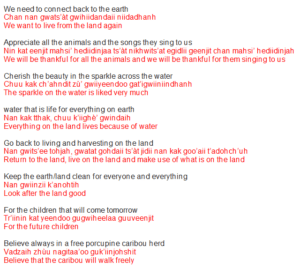

The Future of Gwich’in by Pavlovich and Firth is to be published in the Gwich’in Atlas.

Being over 3,000 km apart, reliable connectivity has proven to be one of the biggest challenges, says Firth a 55-year-old language translator from Teetł’it zheh (Fort McPherson).

Firth logs in from her cabin just outside of town. “Because when I’m out here, it seems like the language is always with me,” she says.

After 30 years working in language, she says she never saw herself as a teacher until now.

For Firth, being out on the land in a camp setting would be the optimal place to learn the language.

“I just think there’s too much artificial intelligence and social media and all these other things,” she says. When it comes to youth involvement she feels many are distracted by the internet.

But Firth doesn’t translate alone: she relies on her lifelong mentor as well —she is 84-year-old Joanne Snowshoe.

Firth says without the Elders, language students are going to have to revert to old stories from decades past.

“It’s going to be tough, but we have a lot of recordings of our Elders’ stories from long ago,” she says, “I think if we want to continue teaching the language, we’re going to have to fall back on those.”

“I could just sit and sew and I’ll just listen to my great-grandmother’s stories that she told in the language and I noticed that really helps with my translating.”

Firth feels that leadership in her community is not prioritizing language and that programs should be afforded to youth all over the Beaufort Delta.

Since the language center in Teetł’it zheh lost its funding and moved to Inuvik, residents haven’t had the same level of access to the archives.

“The Elders told me, ‘Don’t be scared to make mistakes’ because that’s when you’re going to be corrected and then you’ll be able to learn to speak.”

“Some Elders express their appreciation by laughing. They’re not laughing at you,” she says, “they’re laughing because they’re so happy that you’re using the language.”

‘Reviving endangered languages’

Since the program’s inception in 2020, Briony Grabke, spokesperson for the GNWT, says “We have seen a steady and growing interest in the program.”

58 pairs of language speakers have since joined and all nine official Indigenous languages made available.

“The program is the first step in an overarching strategy for revitalizing Indigenous languages in the NWT,” she says. This approach is considered and celebrated as “best practice” and has been recognized worldwide as a successful method for reviving endangered languages.

The program is offered in Dene Kǝdǝ́, Dëne Sųłıné, Dene Zhatıé, Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik, Inuinnaqtun, Inuvialuktun, nēhiyawēwin and Tłı̨chǫ.

The next call for applications will be available in Feb. 2024.