Warning: This article discusses residential schools and can be traumatic, mental health supports are listed at the bottom of the article.

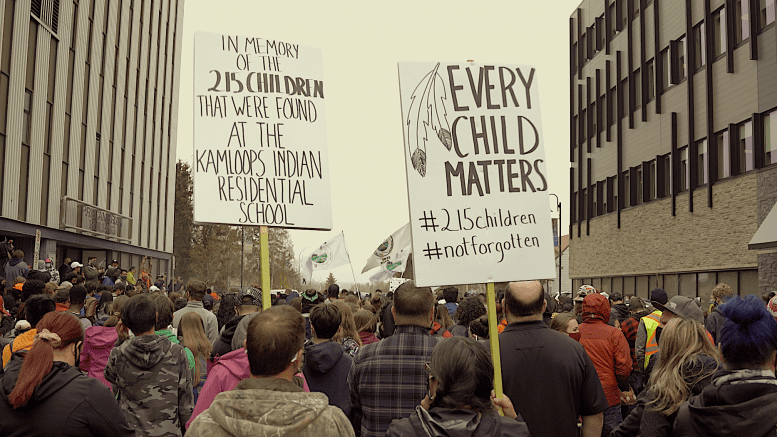

The National Day of Truth and Reconciliation will be an opportunity for people to reflect on Canada’s dark past.

Sept. 30 was officially made a statutory holiday by the federal government to honour the lost children and survivors of Canada’s residential schools.

“Public commemoration of the tragic and painful history and ongoing impacts of residential schools is a vital component of the reconciliation process,” writes the federal government in a press release.

CKLB held a special broadcast focused on Truth and Reconciliation. You can listen to the hour-long show below.

Show notes

Here is some additional information discussed in the program.

- Jean and Roy Erasmus Dene Wellness Warriors

- Secwepemc Honour Song by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc drummers

- Apology by the Catholic Bishops of Canada

- Search for unmarked graves at the residential school site in Deh Gáh Got’îê First Nation

- The new Survivors’ flag

- Andrew Carrier shares his experience with Historica Canada

- Read more of Anonda Canadien’s work and her beading

Essay be Anonda Canadien

Below is a transcript of the essay read by Anonda Canadien on the program.

It’s easy to sit and talk about the struggles of Indigenous people, but that’s not what we’re going to do today. It’s already a heavy day, so we’ll talk about how Indigenous people find comfort and healing in our traditions.

My name’s Anonda and I’m from Deh Gáh Got’îê (Fort Providence), currently working out of Somba k’e (Yellowknife).

As a young Indigenous woman, I grew up learning how to bead and sew from my mom, my grandma and aunties. I went off to school down south when I was 17. I didn’t know what homesickness was until then.

I would wake up with a pit in my stomach, at first I didn’t know what it was or why it was there. Overtime, I realized it was the ache for home. The land with forest evergreens, frozen winters, dusty roads, my community on the river. Most importantly, home is hearing my grandma speak in the language and the smell of smoked moose meat, the sound of the drums and singing. Home is where my culture is.

In my dorm room, I’d have a drum song in the background and try to remember how to bead. How the pattern goes, which bead the needle goes through and how much thread to use. I didn’t understand then, but I was using all these things I was taught as a little girl to connect me to home, to my culture.

Eventually, beading became second nature, like breathing. I felt as if I could bead flowers and intricate designs until my fingers became numb. I was comfortable enough that I taught many of my friends how to bead, and in their eyes I saw the warmth, the comfort it also brought them. I’m always open to teaching those who want to learn and those who need guidance when they struggle. This is something that I will not keep to myself.

I don’t remember how old I was, maybe 11 or 12. I was at a camp in Edehzhie. There was a net set and dozens of fish scattered across the table. I watched as my grandma cut the fish, her hands so skillful and not a bead of sweat on her forehead. It was ingrained in her hands.

I was given a knife and I touched the fish, slimy with its scales and I remember making a face. I was always told to never be proud. I think what they meant was to never make a face and say ‘Ew’ when presented with traditional foods. I cut the fish, watching my grandma and mom and copied their actions.

To this day, it’s ingrained in my mind and in my hands. The feel of the bones cracking underneath my hand at the cut of the knife.

At that same camp, I learned how to make dry meat. It was in a makeshift teepee with tarps and sticks, more like a lean-to with an opening at the top for the smoke to pass. The ground was covered in spruce boughs, I was sitting next to my grandma and mom, and I watched. Once again, I copied their actions as I slid the knife into the meat. It was patchy, but i was so happy and the smile on my grandma’s face spoke louder than words.

To practice these traditions, it connects us to our ancestors. Seven generations back and seven generations forwards, these traditions will be alive and well. This is why I don’t keep the practices to myself, I share with anyone and everyone who wants to learn and listen. Granted, I’m not an expert by any means, but there’s value in knowing that there’s young Indigenous people who think the same as me.

We walk in two worlds. The traditional world and the modern world.

As a friend of mine once said, “It’s hard to navigate the two.” And it’s true. There’s a balance to be made. Sometimes I get so caught up in my work and social media, I forget to take a deep breath to slow things down. To help me do so, I pick up the threaded needle and the pink coloured beads.

My feet pound against the dirt, moving in rhythm with the beat of the drums. I lose myself in the dance, in the circle. I feel every movement, every sound, every breath.

Drum dancing is what makes me feel most at peace, at home.

To practice these traditions is a slap in the face for those who wanted us gone, who tried to kill our culture and our people. Just by breathing, we’ve overcome those who kidnapped young ones to bring them to hell. At the same time however, just by breathing we’re still seen as a threat and another statistic.

We are more than statistics and stereotypes.

When we talk about Indigenous struggles and sorrows, we must also talk about Indigenous excellence and accomplishments. We must also remember that our ancestors gave us more than sorrows.

I recently found a saying along those lines. It said, “We’re our ancestors wildest dreams.”

Historical information and support

The residential school system was in place from 1831 until 1998 and is recognized as an act of cultural genocide.

There have been thousands of children’s bodies found at former residential school sites to date, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates well over 4,100 children have died as a result.

People are encouraged to wear an orange shirt to commemorate the thousands of lost children.

The National Day of Truth and Reconciliation and discussions around residential schools can be a difficult, but there are supports available.

Residential school survivors can call 1-866-925-4419 for emotional crisis referral services.

The Hope for Wellness Help Line offers counselling and crisis intervention to Indigenous people across Canada. This is at 1-855-242-3310 and is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

There is also the NWT helpline that can be reached at 1-800-661-0844.

This story will be updated…