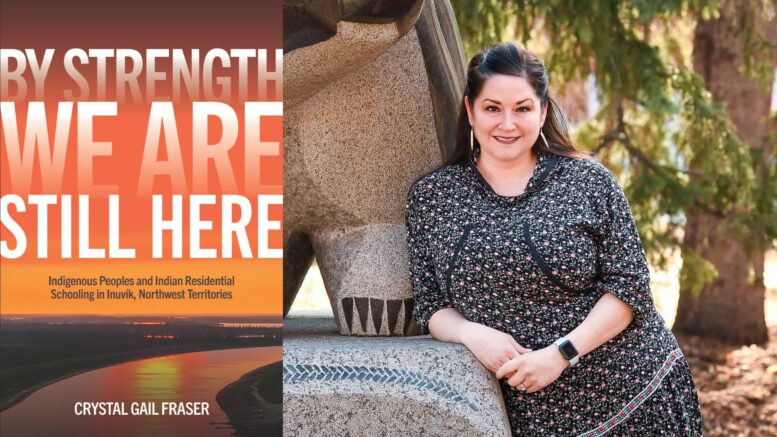

“What would Indigenous societies look like today if the legacy of residential schools – all of the violence, death and trauma – never happened?” asks Crystal Gail Fraser, a Gwichyà Gwich’in historian and scholar at the University of Alberta.

This is a question that lingers on Fraser’s mind. It prompted her to spend a decade documenting the lived experiences of over 75 people impacted by northern residential schools between 1959 to 1982.

The resulting book, By Strength We Are Still Here, is published today.

“I was seeking to better understand my own identity, my family, and colonialism in the northern communities,” says Fraser.

Fraser grew up at her family’s fish camp along the Mackenzie River in Inuvik. Her mother attended Grollier Hall residential school, and her grandmother went to at Aklavik’s Immaculate Conception school.

“Residential schooling in the North was unique from what happened down south because the North had long been left behind in Canadian polity and in settlement,” says Fraser.

In 1948, a joint House of Commons and Senate committee has decided that residential schools were not beneficial for Indigenous children. They published a report that recommended to pause all enrollments in residential schools, and start integrating Indigenous children into municipal or provincial schools.

Yet ten years later, a whole new generation of residential schools started to ramp up in the North, with new structures being built in Yellowknife, Fort Simpson, Fort Smith, Délı̨nę, Fort McPherson, and Inuvik, as late as 1967.

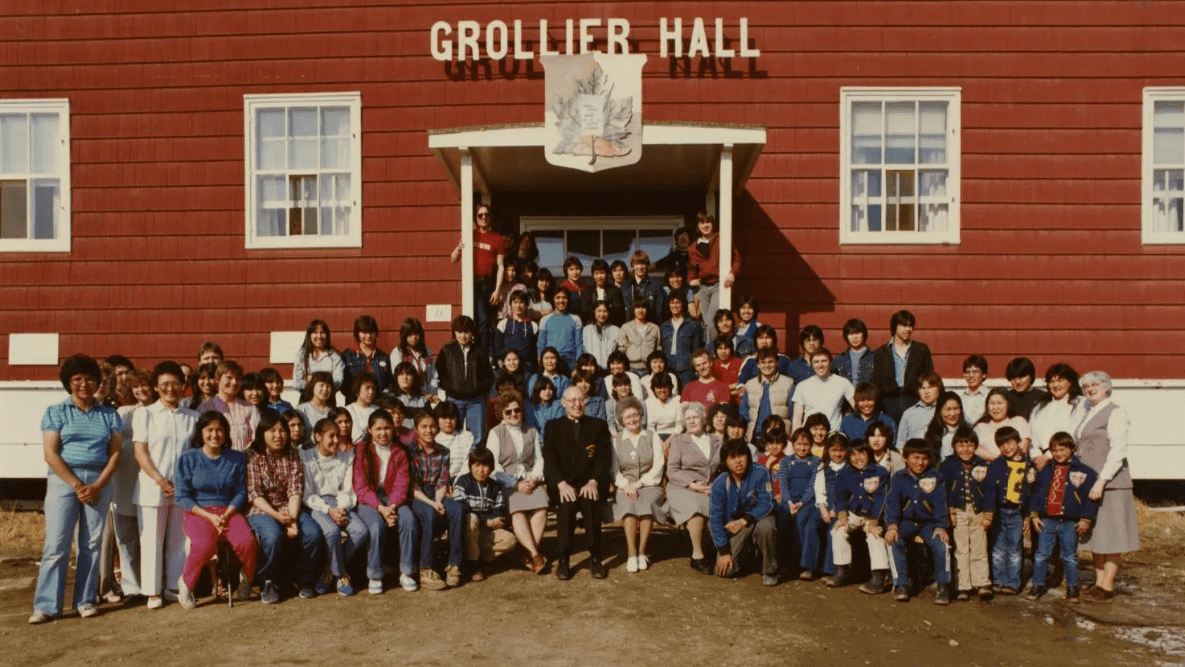

Grollier Hall Residential School in Inuvik closed in 1997, which is one of the last residential schools to close in Canada. (Photo from University of Manitoba’s National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

“One of the reasons why residential schooling continued in the North after it started to wind down in the South was because of this ongoing program of assimilation,” Fraser explains.

“This was part of a Canadian policy that they were still looking to remove Indigenous peoples from the land, making them into English or French speaking Canadian with Christian values.”

Fraser adds that it was also related to Arctic sovereignty as the region became a geopolitical hotspot due to growing interest in the Arctic from the United States and the Soviet Union. For Canada, residential schools were seen as a way to solidify their presence in the North and demonstrate active governance to other nations.

Fraser’s book is the first comprehensive study of northern residential schools, with a focus on survivors of Stringer Hall and Grollier Hall in Inuvik, both opened in 1959.

“I learned that along the way, two things can be true at the same time,” says Fraser. “We had this awful colonial system of residential schools, which tore families apart and tried to destroy our cultures and language that we now know amounted to genocide.”

But on the other hand, Fraser says she sees incredible strength in survivors and Elders in ways in which they responded to their experiences and heal after residential schools.

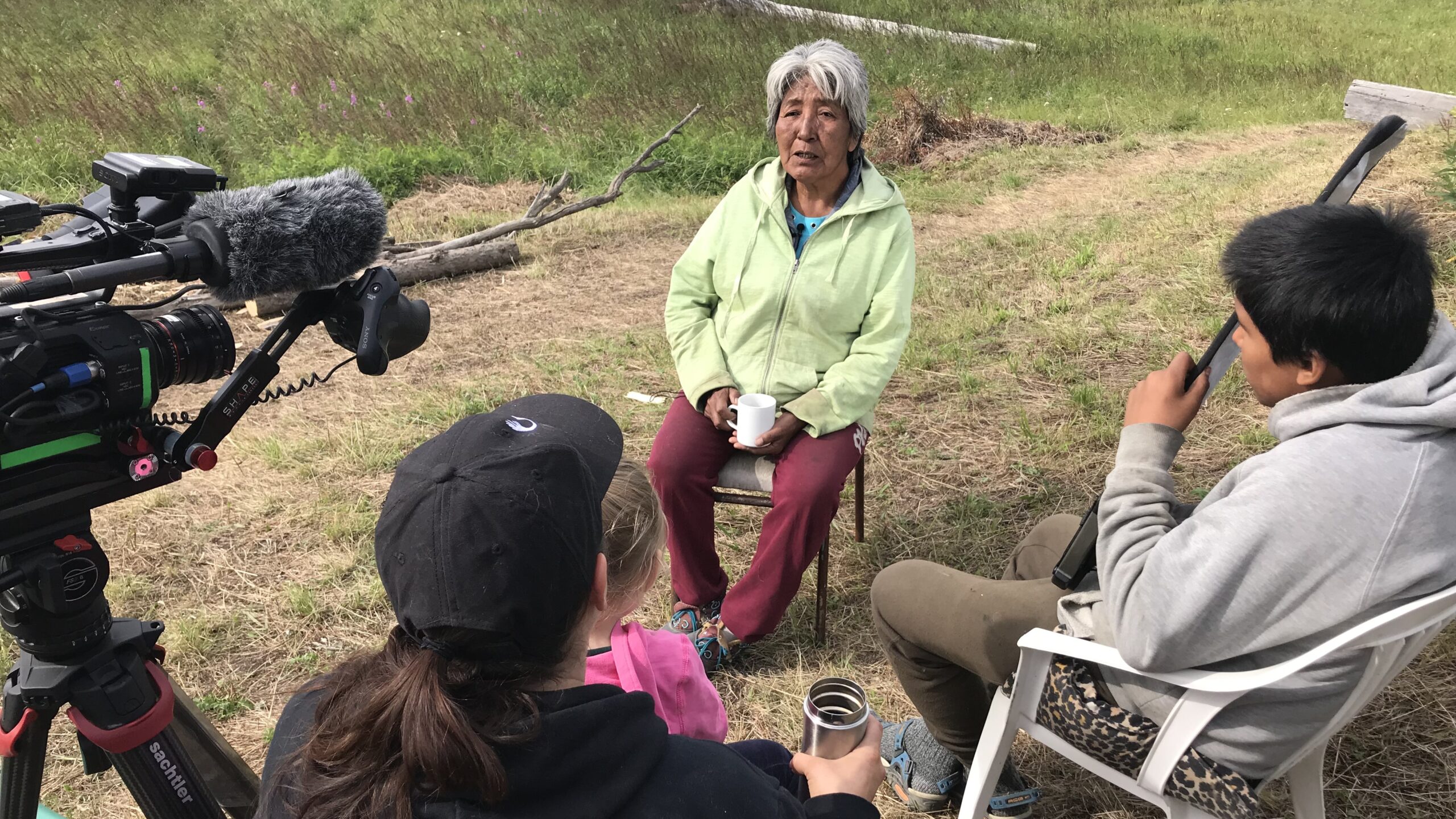

“They were so generous in sharing their vulnerabilities, and I was really honored and privileged to take care of those stories,” she says.

Agnes Mitchell shares stories with Crystal Gail Fraser on the land at Dachan Choo Gę̀hnjik (Tree River, NWT). Photo taken by Megan Fraser. (Photo courtesy of Crystal Gail Fraser)

Fraser conducted all 75 interviews by herself, which “took a lot of time and a lot of care”. During the ten-year process, she has grown as a researcher, a community member, and a mother.

“When my daughter was five or six years old, I would regularly think to myself: this is the time period when the Indian Act said it was okay to take children away,” says Fraser.

“And when my daughter lost her first tooth, I wondered – what did they do with the teeth at residential schools? Who taught kids how to tie their shoelace? Where did children go when they needed a hug?”

The answer would be nowhere she says, as children were not allowed to be affectionate at residential schools.

For her future work, Fraser says she will always be a residential school scholar as “our understanding of residential schools is just beginning”. She wants to deepen her research on Treaty 11, land claims and colonialism in the North.

Fraser is expected to host three book launches across the NWT over the next week. Catch her in Tsiigehtchic on December 15, Inuvik on December 16 and Yellowknife on December 18 at the Explorer Hotel.