Smoked white fish filled the air as seven youths prepared for their first night at camp at Deèzàatì (Point Lake). For many of them, this was their first time experiencing the Hozı̀ıa (Barrenlands) and being away from their home community.

Through a program called Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoehdèe K’è (Boots on the Ground), the students travelled close to the Nunavut border to collect caribou data and contribute to the Tłı̨chǫ monitoring program.

Home base, camp at Point Lake. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

The youth actually reached out to staff at Chief Jimmy Bruneau School to participate in this program.

“I have never seen so much caribou in my life,” said Angel Koyina. “My heart was racing.”

In total, she saw roughly 400 Bathurst caribou in her week at the camp.

Although Koyina has experienced similar programs like this before, she says, what makes this one so unique is the personalized instruction from Elders.

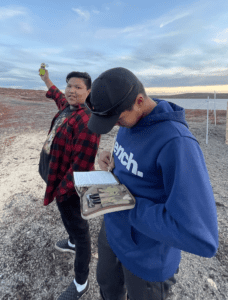

The boys prepare fish for dinner. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

One of the biggest lessons, Koyina says she learned was to always check her surroundings when out on the land and never go to the washroom alone.

She says the experience meant a lot to her, seeing all those caribou, “just getting close to (them) and having pictures of (them) it was pretty cool seeing (them).”

Tylene Tsatthia, another 19-year-old woman, had different reasons for joining the expedition.

“I wanted to get away from the community and be out there on the land, get to learn some new things, new skills and gain more knowledge,” she says.

Afternoon cranberry picking with Elder Therese Zoe. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

Through this experience and in spending time with the Elders, she’s gained a new respect for the land and in herself as a young woman.

“I got to learn from (Elders) who actually know the land and know the (traditional) ways of life,” she says.

Tsatthia’s favourite camp activity was cutting fish, a skill she began honing as a young girl. “I feel like I can cut fish pretty good now,” she laughs.

On their journey, the group also stumbled across burial sites. This was a stark reminder to the students that these lands were travelled since time immemorial.

Students paused at a burial site to pay their respects. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

The group made offerings, sprinkled tobacco and prayed over the graves.

“I re-learned how to be respectful to the land, to myself and others,” she says, “I’ve learned how to survive.”

Chris Stanbridge is the lead organizer for culture programs at CJBS and has been working with these students closely both on the land and in the classroom.

Keegan Tlokka and Leegah Lafferty collect and record daily weather readings.

(Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

Stanbridge says they got accepted to do the program last minute and in two and a half days, he scrambled to get everything ready for the students.

“We just wanted to get students back on the barrenlands,” he says. “When they get up there, it makes it real to them.”

“There’s a little bit of excitement on their faces but nervousness (as well) because students know of the barrenlands, have seen pictures, and heard stories,” he says. But many have never experienced it, firsthand.

“(Elders) shared stories with the students and told them how hard it was to find food at times,” he says, “so I think that really grounded and connected the students.”

He also worked with Tammy Steinwand, director of lands protection with the Tłı̨chǫ Government.

“I really tried to advocate for the students to go out there,” she says. “For them to see what we do as part of the program, how we do our work, what equipment we use, how we travel, all of that.”

Leegah Lafferty doing some map work, plotting caribou movement. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)

She hopes this program and others like it encourage students to get curious about environmental science careers in the future and keep students coming back for more traditional programs.

She acknowledges the difficulty for members of the community to afford this experience on their own.

“If we don’t take them out on these types of trips, they’ll never get to go out,” she says.

Ever since the students from CJBS came back from their trip, Steinwand says other schools have been requesting to do the same program.

The problem she explains is that there is not enough money for everyone in the community to benefit from these programs.

“When they come back, you can see it in how they carry themselves and how they look,” she says, “They’re rejuvenated. They seem to get off the plane healthier.”

The group regularly had tea on the shore, where they shared their findings of the day. (Photo courtesy of Chris Stanbridge)