Two Indigenous MLAs have criticized the government’s affirmative action policy in as many days.

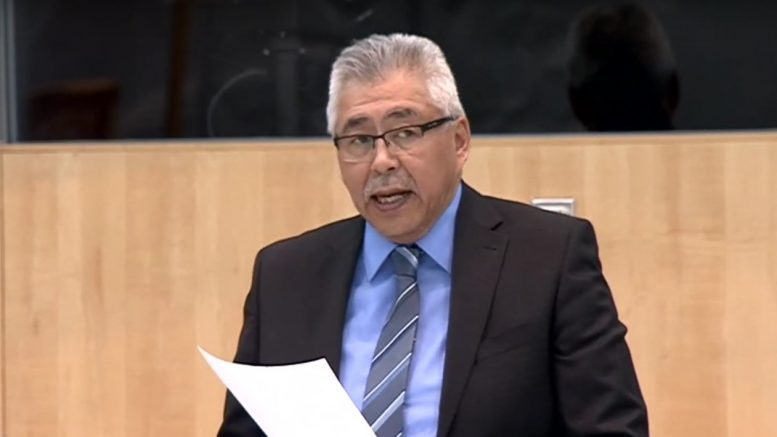

Tu Nedhé-Wiilideh MLA Tom Beaulieu and Deh Cho MLA Michael Nadli took aim at the policy this week in the Legislative Assembly.

“I am not convinced that our government is committed to increasing the number of Priority 1 employees that we employ in our departments,” said Beaulieu.

The policy defines Priority 1 employees (or P1) as “Indigenous Aboriginal Persons”. That language, said Nadli, is “outdated.” Indeed, the policy states any resident is considered “Indigenous” if they’ve lived more than half of their life in the NWT—yes, that means even non-Aboriginal people.

For the sake of this article, we will refer to P1 candidates by the technical term in the policy: Indigenous Aboriginal.

Numbers by department

According to the 2017-2018 Public Service annual report, about 30 per cent of the Government of the Northwest Territories’ 5,091 total employees identify as “Indigenous Aboriginal”. That’s across the entire public service, including departments, education councils, health and social services authorities, and other agencies like Aurora College and the housing corporation.

That ratio has remained stagnant over the life of this Legislative Assembly.

MLA Beaulieu pointed that out in the house, saying, “This government has not developed proper plans to increase the Priority 1 numbers in all departments, boards, and agencies.”

To be fair, Beaulieu was minister of human resources from 2013 to 2015 and the number of Indigenous Aboriginal employees still hovered around 30 per cent during his tenure.

Quantity of P1 employees is one thing, the positions they hold is another. When looking at senior management positions, all of the above figures take a significant drop. Only one in five senior managers identify as Indigenous Aboriginal.

Numbers by region (a.k.a the capital conundrum)

Asked about these figures in the house, Finance Minister Robert C. McLeod diverted the conversation to focus on employees outside of Yellowknife.

And he has somewhat of a point.

There are about 1,100 Indigenous Aboriginal employees outside the capital who make up 48 per cent of the workforce outside the capital.

“As our people start to be more and more educated and get into some of these positions, I think we are going to see those numbers rise,” said McLeod.

However, this fact doesn’t address the issue in Yellowknife where Indigenous Aboriginal people are only 16 per cent of the workforce. Sachs Harbour (17 per cent, or two of 12 employees) and Kakisa (zero of two employees) are other communities with low rates.

Barriers and ‘Aboriginal advocate’?

MLA Nadli said the written requirements to employment is a possible barrier for some P1 candidates. He asked the minister if there are any exceptions for labour positions or similar.

McLeod said he heard of cases where supposed unqualified employees were asked to train new hires for the job they were unqualified to do in the first place, pointing to the confusion in the system. In that case, he said, the unqualified employee did advance despite not having the “paper qualifications.”

“I think that was a good case of applicants and our people moving through the system based on their ability to do the job.”

However, the minister didn’t say what measures would be taken to address these kinds of issues on a broader scale.

Nadli also suggested bringing in a dedicated “Aboriginal employee advocate” to work with government to boost the representation of Indigenous Aboriginal people in the workforce. The minister said he didn’t know if there was a dedicated advocate.

CKLB found the government already has an Indigenous Employee’s Advisory Committee, whose stated purpose is to give “strategic advice to the GNWT on strategies and approaches to attracting, recruiting, advancing and retaining Indigenous employees within the GNWT.”

The committee has been in place since 2009. In the 2008 public service annual report, again Indigenous Aboriginal people only made up about 30 per cent of the workforce, calling into question the advisory committee’s effectiveness.

While the annual reports give a snapshot of the current workforce, MLA Beaulieu pointed to the lack of representation and its effects on young Indigenous people wanting to access the system.

“In our small communities, we encourage our students by telling them to go to school every day and graduate from high school, in order to provide themselves with an opportunity to take post-secondary studies,” he said. “However, we cannot in good faith tell them they have opportunities with the GNWT, because the actions of various departments do not project a welcoming environment for Indigenous people.”

Francis was a reporter with CKLB from January 2019 to March 2023. In his time with CKLB, he had the immense pleasure and honour of learning about northern Indigenous cultures.