The Dene Nation is kicking off a project to document the building of the Canol Pipeline from the Shútagot’ıne perspective — and the grandson of one of the original guides is leading the way.

Edward Blondin, George Blondin, Paul Wright, these were some of the guides that helped the American military plan the route of the pipeline and support the building project.

A respected Elder, knowledge keeper, and writer, it’s one of George Blondin’s lesser-known pieces of writing that today is helping guide the journey of documenting the Dene role in the pipeline.

Before time runs out

Tim O’Loan has spent years reconnecting with his Shútagot’ıne roots.

Tim O’Loan is George Blondin’s grandson. He will be collecting stories of the Dene that helped guide and support the construction of the Canol Pipeline. (Photo courtesy of O’Loan)

In the 1950s, after the pipeline was built and abandoned, O’Loan says his grandfather George Blondin moved to Yellowknife so his children could have better access to education and healthcare.

“Sadly, when he got here all of his children, including my mom, were taken away to residential schools,” says O’Loan.

He says his mother Bertha Blondin gave birth to him at a young age in Edmonton, “ripe for the Sixties Scoop era.”

“As a product of the Sixties Scoop,” he says, “that was something that I had to pursue, ‘Where do I come from?”

O’Loan moved to the NWT and reconnected with his Blondin family, including his grandfather George.

“What’s fascinating is my grandfather has written a few books, and one of the things that is fairly new to us is the fact that he kept a diary of his time supporting the American military,” says O’Loan.

In 2006, O’Loan moved to Ottawa. Two years later, George Blondin passed away but his diary lives on and O’Loan is using it as a basis to reach out to some of the families involved in the project.

“Let’s be very clear about this, I’m not sure if the Canol could have been built without the Dene,” he says. “These stories and the Dene involvement needs to be captured before time takes away all of those stories.”

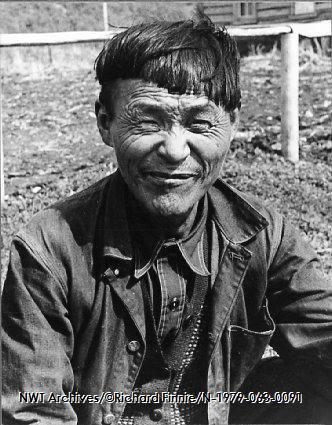

- Johnny Hotty was a guide from Tulita. Photo taken June 11, 1942. (NWT Archives/Richard Finnie fonds/N-1979-063: 0091)

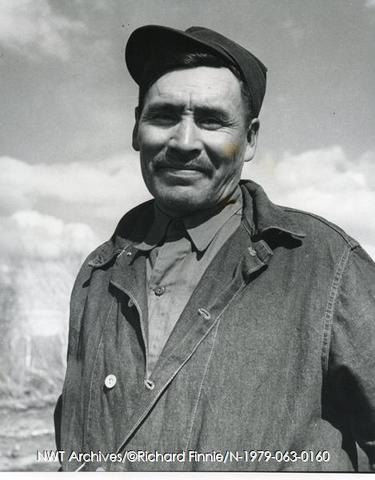

- Fred Andrew, a guide from Tulita, who accompanied Guy H. Blanchet, D.L.S. on dog team reconnaissance from Canol Camp to Sheldon Lake in October/November 1942. (NWT Archives/Richard Finnie fonds/N-1979-063: 0160)

History not truly told

The federal government recently announced $25,000 in funding for Dene Nation to carry out the project.

“A part of our history as Dene people has not truly been told to the world,” says Dene National Chief Norman Yakeleya.

Despite their traditional knowledge being crucial to the project and guiding engineers through the mountains, Yakeleya said the Dene “weren’t treated with much respect.”

“They lived under extreme conditions, they worked under extreme conditions, and they weren’t given much worth in regards to helping the Americans get the oil from Norman Wells to Whitehorse,” he says. “A lot of unsung heroes weren’t in our history books.”

Still today, he adds, anyone who researches the Canol Pipeline and comes across American information, there’s no mention of the Dene.

While the final format of the collected stories has not yet been determined, part of the project will be to install monuments in Norman Wells and at the Canol trail head as reminders.

Leaving their coffee cups

Yakeleya also organizes an annual hike along the trail for youth to see first-hand what their ancestors helped build, and reconnect to the land.

O’Loan says he and his son would like to do the hike one day.

“Not having a traditional upbringing, it’s an honor to go into our traditional territory and just to be able to go and capture the stories, not only of my grandfather, but others as well,” he says.

The pipeline was built between 1942 and 1944 and was abandoned in 1945 after only 13 months of being in operation.

- A Caterpillar tractor fitted with a plow pulls a supply train of pipe, destined for use in the Canol pipeline, across Great Slave Lake in April, 1943. Overflow sits atop the lake ice at a point somewhere between Fort Resolution and Hay River. (NWT Archives/Sam Otto fonds/N-2004-026: 0039)

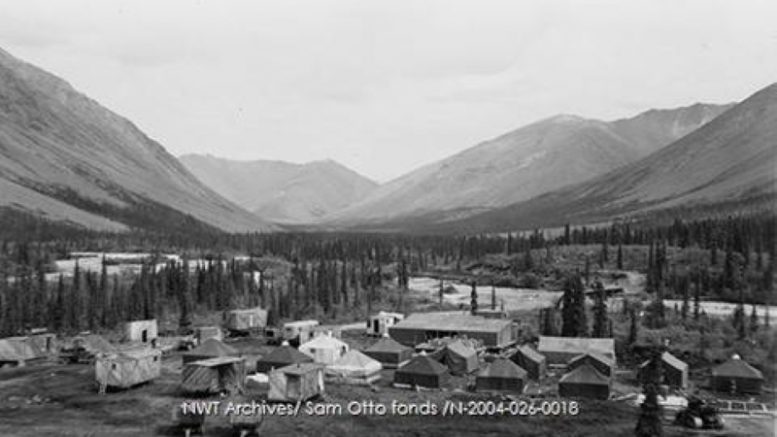

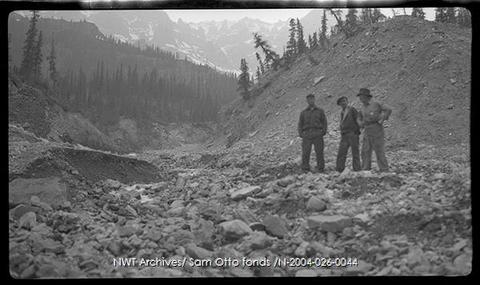

- [Three men working on the Canol Project stand in an area recently cleared for the roadway. (NWT Archives/Sam Otto fonds/N-2004-026: 0044)

“The United States got up, left their coffee cups on the table, walked out and left everything as is,” says Yakeleya.

Hundreds of kilometres of wiring, oil barrels, even trucks and other machinery was abandoned at the site. While an official clean up effort started in 2018, Yakeleya says there’s still much to do.

“Total disrespect for the Shútagot’ıne people and their land,” he says.

One day he’d like the U.S. government to take ownership of that disrespect, but for now “that’s another fight for another day.”

The documentation project will wrap up next summer.